Disability is a loaded word.

I won’t debate the semantics of the term, what the current politically correct term is, or how to make your workplace more variant friendly.

Let’s talk about something far more inflammatory. The rights of the disabled to carry out adult relationships. At best, a disabled person is able to find a partner despite their difficulties, marry (or not), and live a happy adult life together, with or without kids (popular example: the TV show Little People, Big World). Sometimes, it’s disabled people fighting in court for the right to marry or raise their own children (the movie I Am Sam). At the very worst, it’s vulnerable people being preyed upon, taken advantage of, or controlled to the point of involuntary sterilization.

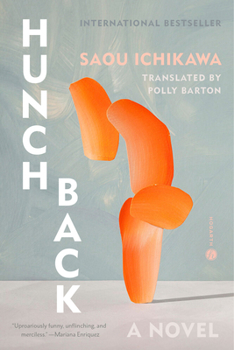

I grabbed the book Hunchback, partly because it was short, and partly because I’ve been in the field of disabilities for 40 years. Hunchback, a novella by Saou Ichikawa, was not the book I’d expected, despite winning multiple awards. Ichikawa’s character, Shaka, suffers from congenital myopathy (same as the author—write what you know), which has left her with progressively weak muscles. Her back is so hunched over she can’t breathe when holding a book, and she spends half the day using a ventilator. She can walk short distances, but her body is twisted and one leg is far shorter than the other. She has a tracheostomy, which makes talking difficult, so she uses a lot of alternative communication devices. Shaka spends her time writing erotica online, the money from which she spends on food for poor people and women.

Winner of several Japanese awards, Hunchback calls out ableism on many levels. Ichikawa considers it political: Disabled people are hidden away by society, never considered because they’re never seen. People in wheelchairs are rarely mentioned in literature at all, unless they’re being “cured,” like in Heidi or A Secret Garden. Disabled people are portrayed as a drain on society, dependent on charity, so by making a wealthy disabled character (who generates income through pornography), she pokes a hornet’s nest.

Another book that touches on the subject of sexual autonomy is James Cole’s Not a Whole Boy. Cole was born in the 60’s with a severe case of exstrophy – most of his organs were born outside his body, and his pelvis malformed. Most babies with this condition do not survive. Due to Cole’s mother’s determination and a great team of doctors, Cole managed to thrive despite severe obstacles. While he seemed more or less normal to other kids, Cole hid the fact that he had double ostomies – all his waste was collected in bags, as he didn’t have the needed parts and couldn’t use a toilet. As he got older and puberty kicked in, it became necessary to undergo multiple surgeries just to have a sense of comfort, normalcy, and proper biological function. Cole’s book documents his struggles with medieval children’s hospitals, lack of pain management, and his eventual success with a career in art and film – certainly not hidden away.

A book that took me by complete surprise was Riva Lehrer’s Golem Girl, a golem being a creature formed from dirt or clay. Riva was born with Spina Bifida in 1958, a time when most afflicted infants did not survive, and almost certainly didn’t walk. She suffers dozens of painful surgeries to keep her mobility, most of which do nothing to ease her issues – she’s just a guinea pig for the surgeons. Although she attends a grade school for the disabled (disability laws hadn’t been written yet), she attends a mainstream high school, then university, where she gets a degree in fine art, all while dealing with surgeries and intense feelings of revulsion toward herself. Amplifying it is her mother’s overprotective codependency, spitting out helpful comments such as “You don’t need a nose job. No one wants to marry a cripple,” and “You shouldn’t have children; pregnancy will just mess up your spine worse,” – culminating in an involuntary hysterectomy at 15 on the mother’s order.

Riva goes on to have multiple affairs with both men and women. While some relationships work out, many times she’s still hit with prejudice – “I can’t love a cripple.” Riva remains unstoppable. She becomes more comfortable with herself through meeting up with other people – often activists – with disabilities. As an artist, she gains renown (and awards) through her paintings of disabled people (and others) she has met.

This book was so hard to put down, and read like you were in the middle of a conversation with her. Lehrer doesn’t go into detail on her disability or surgeries; she talks about herself, not her medical issues. After doing time as an anatomical artist, she sees people not so much as disabled, but as human variants – no one is “normal,” there is no “normal,” just human variations. But everyone has a right to love and happiness.

At the heart of it, people with physical disabilities are still people. It doesn’t mean they don’t have the same dreams, desires, or feelings as people who aren’t. All of these books will give you deep new insights into the strength of humanity.

Thank you for the kind words on my memoir. Very appreciated. Riva

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Able and Willing | Camp Chaos Rules