Roald Dahl is an author of controversy. He’s lauded for being a brilliant writer; he’s shunned because of his 1920’s upbringing and racist and antisemitic writings and comments. His children’s books are considered classics of literature; his children’s books are ignored by some who complain they are too dark for children’s literature.

Too dark? Let’s look at this.

Little Red Riding Hood’s grandmother was eaten by a predatory wolf, Cinderella’s stepmother made her into a slave, Hansel and Gretl were abandoned (twice!) by their parents and taken in by a cannibalistic hag; the Little Match Girl freezes to death all alone. Is Charlie and the Chocolate Factory or Matilda darker than that? Not quite.

There is some truth to it – in many of Dahl’s stories, parents, if not most adults, are seen as evil, or cruel, or incompetent providers – mean teachers, poor and ever-working parents, buffoonish adults who cannot see the plight of the child (Wonka is most definitely – well, Wonky). There are elements of racial bigotry (the tiny black (yes, they were black in the book) oompa loompas living on grubs; Germans always being fat gluttons, etc). But is this so far from other children’s stories? Not so much. Lemony Snicket’s Series of Unfortunate Events is also darkly humorous, and few are crying foul. Dr. Doolittle bleaches a man’s skin, rather than let a black man marry a white woman. Peter Pan’s stereotypical depiction of Native Americans is downright painful and offensive on many levels. Bigotry and stereotyping is nothing new, only that fact that we now call it what it is.

One point to remember is that parents, quite frankly, are a pain in the neck to children. They love them, while at the same time resent them for setting limits, saying no, and dragging children kicking and screaming through the process of growing up. For Dahl – and millions of others – who grew up in British boarding schools, at the mercy of bullies they couldn’t escape and teachers who were allowed to whip children, the experience left a more lasting impression (Pink Floyd, anyone?). For those in Britain who grew up in World War II, who as children hid during the Blitz or were shipped out to board with strangers, it lends another level of abandonment and trust issues to children’s literature. There’s a reason behind a lot of the dark – and for British children, it’s a shared cultural memory. Is Fantastic Mr. Fox an allegory for the war? Possibly.

Another point to consider is children are the hero of their own story. It’s fine if Daddy vanquishes the dragon, but children would much rather be the ones doing it. Tween and Pre-tween children desperately want to be seen as competent, able to impress grown ups with their abilities. Children want to be the hero, and they can’t do that if Mummy and Daddy are with them telling them no – hence the number of orphan stories, or children alone. They can’t rely on the adults with them, or the story won’t work. A story about a child who tried and failed, who gave up and lived with their perceived oppression, isn’t a story a child wants to read about. There’s no role model there, no hero, no inspiration, no one to pretend to be. So of course Matilda has to shine, and the Peach must kill James’s wicked aunts, even if he has to find kinship with a bunch of insects, and even wacky Mr. Wonka can’t miss the good that dwells in Charlie.

Darkness, shmarkness. The world is a dark place, and childhood a relatively new invention. In too many places, children are still locked in war-torn places, famines, camps, drug violence, and abusive situations. Our lauded fairy tales of yore – right down to Mother Goose and Aesop’s Fables – hark back to far darker times.

Let them read. If nothing else, darker literature provides the perfect chance to discuss empathy, fantasy vs. reality, and handling tough situations – including some of the tough times we’ve been through in the past year.

Danny the Champion of the World

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

I used to enjoy cooking and baking once, but life happened (as it does), and over the years it evolved from a fun hobby into a chore. I’ve bounced back from my low point of lockdown-era frozen buffalo chicken strips, but cooking is still not something that brings me joy. Even when I try new recipes. No, especially when I try new recipes. There’s too much thinking, too many variables, not enough autopilot. I groan whenever my produce subscription boxes send me yet another unidentifiable root vegetable that requires a consultation with the internet. And if a new recipe starts going sideways – I’m looking at you, butternut squash gnocchi that I made for Christmas – I tend to season the cooking process with a heaping spoonful of expletives.

I used to enjoy cooking and baking once, but life happened (as it does), and over the years it evolved from a fun hobby into a chore. I’ve bounced back from my low point of lockdown-era frozen buffalo chicken strips, but cooking is still not something that brings me joy. Even when I try new recipes. No, especially when I try new recipes. There’s too much thinking, too many variables, not enough autopilot. I groan whenever my produce subscription boxes send me yet another unidentifiable root vegetable that requires a consultation with the internet. And if a new recipe starts going sideways – I’m looking at you, butternut squash gnocchi that I made for Christmas – I tend to season the cooking process with a heaping spoonful of expletives.

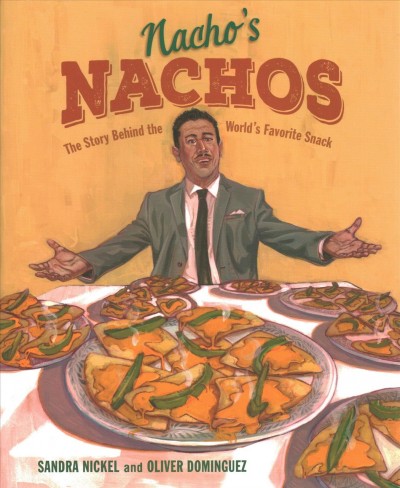

Celebrating 80 Years of Nachos, this book introduces young readers to Ignacio “Nacho” Anaya and tells the true story of how he invented the world’s most beloved snack in a moment of culinary inspiration.

Celebrating 80 Years of Nachos, this book introduces young readers to Ignacio “Nacho” Anaya and tells the true story of how he invented the world’s most beloved snack in a moment of culinary inspiration.

If you haven’t read him, Pete the Cat is a groovy large-eyed, laid-back blue/black cat who lives with his mom and dad and his tuxedo-patterned brother Bob. He has a host of friends (Grumpy Toad, Gus the Platypus, Callie, Squirrel, etc) and he loves bananas and surfing. His stories are mostly easy-readers that play to the 2-7 year old crowd, but he is infinitely more interesting than that. Pete is the kind of story you want your child to like, because you want to read more of his stories.

If you haven’t read him, Pete the Cat is a groovy large-eyed, laid-back blue/black cat who lives with his mom and dad and his tuxedo-patterned brother Bob. He has a host of friends (Grumpy Toad, Gus the Platypus, Callie, Squirrel, etc) and he loves bananas and surfing. His stories are mostly easy-readers that play to the 2-7 year old crowd, but he is infinitely more interesting than that. Pete is the kind of story you want your child to like, because you want to read more of his stories.