The FDA has been under increased scrutiny in recent years. When discussing its value and the ways it promotes public health, it’s important to dive into its history.

A hundred years ago, infant mortality in New York City was 25% – one out of FOUR children would die before the age of one. While diphtheria, whooping cough, measles, small pox, mumps, polio, scarlet fever, cholera, and pneumonia were as common as fleas in crowded, dangerously sub-divided tenements, the greatest cause of infant mortality was… milk. Toxic milk.

Back then, cows were often fed cheap “swill” – the discarded mash from distilleries. Sometimes it was still boiling hot, and needless to say, it made cows – who stood in filth up to their bellies and were often tubercular and covered in udder abscesses – malnourished and ill. They gave off a rancid, thin, blue-gray milk that had no nutritive value. To counteract public opinion, it was often “recolored” with chalk or even plaster. Bread was full of fillers such as sawdust, alum, and plaster. Spoiled meat might be colored up with toxic copper. Lead, copper, and mercury were used to color candies.

Babies died.

Enter the Pure Food and Drug act of 1906. Partly fueled by the nascent science of chemistry which could detect what was really in the food, and partly by the publication of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, a novel based on real events that exposed the horrific true conditions of the Chicago stockyards and meat packing industry, people began to raise a stink about the condition of their food supply. Teddy Roosevelt, a libertarian at heart, was opposed to regulation. He was heavily lobbied by the industries, but eventually signed laws against selling tainted food. Milk, a major spreader of tuberculosis, had to be pasteurized if it was to be sold across state lines. Meat could not have more than a minute amount of contamination. Items sold as remedies had to list their actual ingredients. Infant mortality dropped by 68%.

By 1938 (note: 32 years later), the US Food and Drug Administration was created after more than 100 people died from cough syrup that used anti-freeze as a sweetener. Because of legal loopholes, the only law it broke was mislabeling. The FDA was in charge of overseeing and regulating food, drugs, and cosmetics, making sure that such items were safe for the general public, to the wails of businessmen. The FDA was designed to work alongside the US Department of Agriculture, founded under Abraham Lincoln. Hairs are often split between the two, pushing responsibility back and forth. When a food poisoning outbreak was traced to frozen pot pies, the blame was focused on the FDA for not watching the factory. BUT, the culprit was further traced to the grain in the crust, and grain safety falls under the USDA.

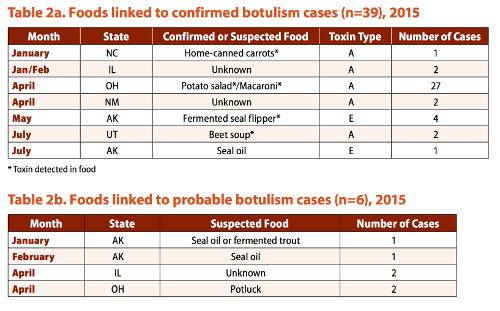

It is almost impossible to eradicate all sources of food poisoning. Chickens can be born Salmonella positive. Listeria survives in soil, then gets tracked on animal feet and into your food. The toxic dose of botulism – that thing people willingly inject in their faces to paralyze muscles? – is so minute it is measured in nanograms (that’s a billionth of a gram. A raisin is about one gram, so think of a raisin in one billion pieces). One single gram – a raisin’s worth – can kill more than a million people. Food poisoning – usually through inadequate cooking – kills more than 3,000 people a year, with an estimated 48 million illnesses in the US alone. As always, children and the elderly are most at risk, as many of these bacteria target kidneys.

Every law regarding food safety –every law – has been enacted because people have been sickened or killed by toxic food. Sellers are trying to maximize profit, and since most US food is owned by a small number of companies (just 4 companies own 90% of US meat production), they can afford an unstoppable army of lobbyists to pressure lawmakers to vote against public interest. So what can you do? Buy from quality sources. Read your labels. If your bread doesn’t mold in 5 days (like all those name-brand hot dog buns), consider it suspect for chemical preservatives, approved or not. Know that meats should be cooked to a specific temperature (depending on the meat), and that no food – hot or cold – should be left out more than 2 hours, probably less in hot weather.

Think you don’t have to worry? Frozen food was recalled last September because six people had died from listeria contamination. In November, more than 10 infants were infected with botulism from baby formula. Poisoned food kills. Support the agencies fighting for you.

Check out these books, and keep yourself informed!

Protecting America’s health : the FDA, business, and one hundred years of regulation by Philip J. Hilts

Eating Dangerously: Why the Government Can’t Keep Your Food Safe, and How You Can by Michael Booth

The Poison Squad by Deborah Blum

Death in the Pot by Morton Satin

Outbreak: Foodborne Illness and the Struggle for Food Safety by Timothy Lytton

Swindled: The Dark History of Food Cheats by Bee Wilson

The Jungle by Upton Sinclair

Poisoned: The True Story of the Deadly E. coli Outbreak That Changed the Way Americans Eat by Jeff Benedict