I finished reading my last book of the year on December 27 (Sugar, Salt, Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us, by Michael Moss, which was very good), and figured that was it for the year. I had too much going on to rush another book but I just couldn’t go without reading something, so I grabbed one off my To Be Read shelf – Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, which has so many recommendations the cover should be 14-carat gold.

Every review was correct. I read the book in a day and a half – I probably could have finished it in five hours, if I’d had uninterrupted time. I just could not put this book down. It’s a sparse novel about a father and son in a post-apocalyptic world – you don’t even find out what happened – as they try to survive travel on foot an unknown distance to the south shore to get out of the freezing winter weather. I’m guessing by the fact they crossed over high mountains they were heading to California, but no clues are given (in the movie, the map shows Florida). This book was beyond compelling, certainly worthy of every accolade. But I didn’t feel like writing an entire blog post about it. Nothing is worse than a review that gives a play by play recap of a book.

So I went and looked up books like The Road, because I’ve read enough post-apocalyptic fiction to have covered all the basics. What is it compared to? For decades (and arguably still) my favorite novel of all time, by number of rereads, is Alas, Babylon, by Pat Frank, a post-nuclear war novel from 1959. A little dated, but not much. In the chaos of 9/11, I sent my oldest friend a two-word text: Alas, Babylon, and he knew exactly what I meant.

But a couple of similar-to lists had the nerve to list Earth Abides, by George R. Stewart. My father was always after me to read this one, the Alas, Babylon of his youth, before the Cold War. Eventually I did, and honestly, it’s one of the worst apocalyptic books I’ve ever read. Okay, maybe they didn’t realize in 1949 that you should never dust pregnant women with DDT. The chemical world was still pretty much in denial that some things were deadly. But these “survivors,” instead of focusing on long-term survival, worry only about immediate needs and then go hungry when canned food runs out. They have no concept of gardening, let along farming and food storage. They think nothing about education, don’t teach their children even basic reading skills, and so that, although they have public libraries to learn survival skills from, in just one generation, no one can read the books. It’s difficult to root for their survival… After learning what to do and how to do it from Alas, Babylon, I truly hated this book.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t other really good books (and movies!) out there. And post-apocalyptic doesn’t necessarily mean science-fiction. Stephen King’s The Stand can be drama, horror, alternative history, Christian fiction, speculative fiction, or loosely science fiction, depending on how you want to interpret it. Same with The Road: It’s a story about father-son relationships, survival during hardship, and climate destruction.

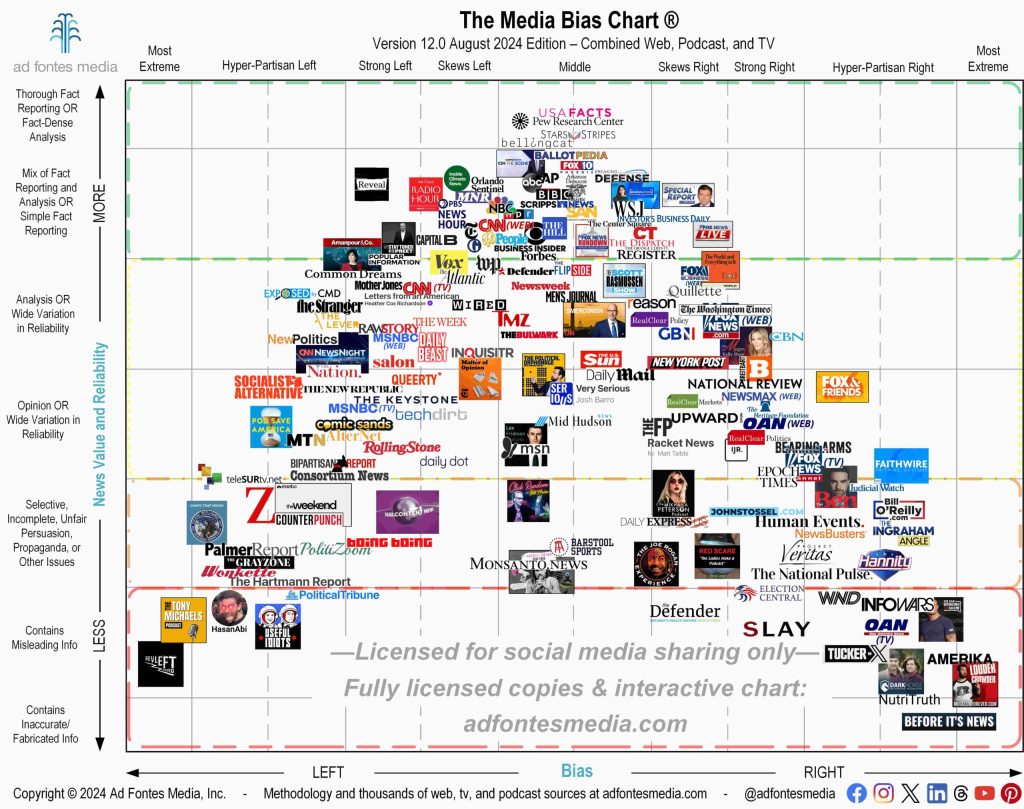

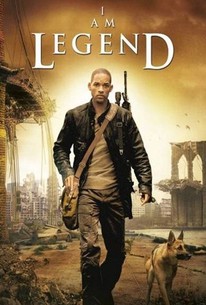

Post-apocalyptic fiction simply means that some calamity has befallen society, tearing apart what used to be normal. If a country – China, Turkey, Peru, Afghanistan, etc. – was utterly destroyed by earthquake and subsequent famine and plague, you could call their recovery post-apocalyptic, even though the rest of the world continued. How we formed trade networks and moved to online commerce during the Covid epidemic can be seen as apocalyptic in a way; we are in a post-apocalyptic society from Covid, as many of our bedrock companies folded, telehealth and working from home became a thing, and society as a whole changed. There are many, many excellent “post-apocalyptic” stories out there, some focusing on disease ( The Andromeda Strain), on climate (Day After Tomorrow), natural disasters (asteroids, etc.) (Solar), nuclear holocaust (Planet of the Apes), the death of oil (Road Warrior), electromagnetic pulse (One Second After), and more. How do people adapt? Can mankind survive? What determination does it take? How can you stay hopeful in the face of annihilation? What can we learn from these stories to avoid such scenarios, or how to survive them? Apocalyptic fiction can be quite imaginative (Hunger Games), and appeal to a wide range of readers (and viewers). Sometimes the book is meh, but the film is far better (Planet of the Apes, for one), sometimes the book is excellent but the movie is okay (Girl With All the Gifts), and sometimes there is more than one film version of the book, with differences between them (The Stand, Planet of the Apes, Day of the Triffids, War of the Worlds). All of them will question your morality and make you wonder about your ability to survive a serious disaster.

(Fun fact: the final battle in War of the Worlds was filmed at the old Uniroyal plant in Naugatuck, CT)

Here’s a wide array of post-apocalyptic novels and films sure to keep you engaged. Which do you like best?

Films (some from novels):

Books (some with accompanying films):