Feeling bombarded? Feeling like every minute of every day someone is throwing information at you, demanding your attention? Do you feel like you have to “Like” everything, or that you want to hide in a closet just to catch your breath? If it’s not a skewed news headline, it’s an unwanted advertisement. Throw in AI-generated content, and how do you even know what’s real and what’s fake anymore?

Deep breath.

You aren’t alone.

And there are ways around it.

Cheshire Public Library recently hosted a talk by John B. Nann on exactly that – Navigating the News, and how to trust what you’re hearing and seeing is real. It doesn’t matter if you swear that headline makes total sense. It doesn’t matter if you’ve seen similar photos on the news. It doesn’t matter where you fall on the political spectrum – anyone can be easily manipulated by false or heavily biased information. Here’s an example: Would you approve of your seven year old’s school class watching a movie about a girl who kills an old woman, then joins up with a bunch of dysfunctional friends to kill again – on screen, in technicolor?

No? Opposed to that? Angry that some people would be okay with that?

That’s the plot of the movie The Wizard of Oz. It’s all in the wording, and you’re not alone if you fell for it.

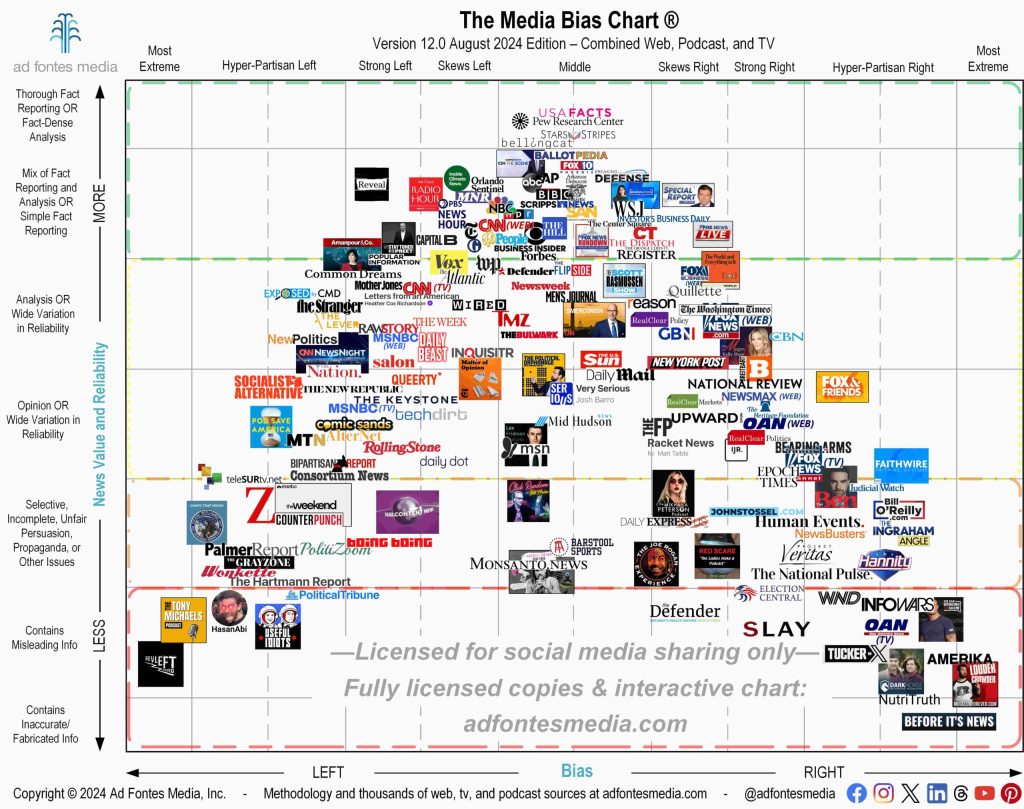

If you’re on social media, you may have seen the Media Bias Chart. Professional media analysts have decided (in sometimes hard to read print) where a source is on the spectrum of a) fact and b) political bias. The further you get from the middle – either side – the less likely what you’re reading is actually true, and more likely you’re reading propaganda deliberately meant to upset you. Let’s face it – calm, soothing news doesn’t sell copy or clicks. Mainstream, respected media such as Time, Newsweek, Wall Street Journal, The Hill, MSN, Forbes, BBC, tend to be factual and reliable. If the headlines on your paper start with “Bigfoot Gives Birth to Alien Werewolf Baby,” you should probably consider it suspect.

Don’t feel like digging for truth? Run the idea past Snopes.com, which relentlessly searches for facts, and facts only.

If a photo looks sensationalized or “off”, do a reverse photo search (Google image search). It’s possible the photo has nothing to do with the claim, or is outdated, or happened somewhere else. Here, in a viral photo, the ship is not dumping waste into the ocean, but churning up sediment with its turbines before anchoring. Check the dates on articles – articles can sometimes reappear ten years later. Sorry, that celebrity died 8 years ago. It’s not news.

Another way to check for devious sites involves looking at the URL – the website address in the search bar. Look at the last letters. If there’s a two-letter ending after a dot, the source is questionable. Every country has a country code, or domain. You won’t see it on domestic sites, but the code for America is .us. Russia is .ru, China is .cn, Rwanda is .rw, Moldova is .md, not to be confused with Maryland. If it’s not coming from the US, it could be a scam. The .co code is technically for Colombia, but it’s often used when companies or organizations can’t get the .com address they want. Approach these sites with an extra grain of salt.

On The Media, a podcast by WNYC, New York Public Radio 93.9 FM, lists the following points to think about:

- Big red flags for fake news: ALL CAPS, or obviously photoshopped pics.

- A glut of pop-ups and banner ads? Good sign the story is pure clickbait.

- Check the domain! Fake sites often add “.co” to trusted brands to steal their luster. (Think: “abcnews.com.co”)

- If you land on an unknown site, check its “About” page. Then, Google it with the word “fake” and see what comes up.

- If a story offers links, follow them. Garbage leads to worse garbage. No links, quotes, or references? Another telltale sign.

- Verify an unlikely story by finding a reputable outlet reporting the same thing.

- Check the date. Social media often resurrects outdated stories.

- Read past headlines. Often they bear no resemblance to what lies beneath.

- Photos may be misidentified and dated. Use a reverse image search engine like TinEye to see where an image really comes from.

- Gut check. If a story makes you angry, it’s probably designed that way.

- Most importantly, if you’re not sure it’s true, don’t share it! Don’t. Share. It.

Finally, here are the resources included on the handout Mr. Nann passed out after his presentation at CPL. Stay informed!

Navigating the News, a presentation at the Cheshire Public Library

John B. Nann, MSLS, JD, LLM, retired law librarian

Organizations and other resources

- News Literacy Project, https://newslit.org/.

- Check, Please! Starter Course, https://www.notion.so/Check-Please-Starter-Course-ae34d043575e42828dc2964437ea4eed

- Web Literacy for Student Fact Checkers, https://webliteracy.pressbooks.com/.

- Stony Brook Center for News Literacy, https://www.centerfornewsliteracy.org/resources/.

- Stanford Civic Online Reasoning Curriculum, https://cor.stanford.edu/curriculum/.

Sources used in presentation

- Mike Caulfield, Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers, https://pressbooks.pub/webliteracy/

- EAVI – the European Association for Viewers’ Interests, Various reports, lesson plans, infographics, guides, etc., https://eavi.eu

- Dan Evon, Three Practical Ways to Detect and Debunk Misinformation, News Literacy Project, https://newslit.org/news-and-research/three-practical-ways-to-detect-and-debunk-misinformation

- Cody Hennesey, Fake News: Bringing media Literacy to the Classroom, Center for Teaching and Learning, https://teaching.berkely.edu/fake-news-bringing-media-literacy-classroom

- Melissa Laidman, Keeping up with …. Misinformation, Association of College and Research Libraries, https://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/keeping_up_with/misinformation

- Cindy Long, Helping Students Spot Misinformation Online, National Education Association, https://www.nea.org/nea-today/all-news-articles/helping-students-spot-misinformation-online

- Research Guide, Misinformation, Bias and Fact Checking: Mastering Media Literacy, University of Oregon Libraries https:researchguides.uoregon.edu/medialiteracy/misinformation-and-disinformation

- Christian Scheibenzuber, Srah Hofer, NicolaeNistor, Designing for Fake News Literacy Training: A Problem Based Undergraduate Online-Course, Computers in Human Behavior (2021), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9761900/pdf/main.pdf